Mystery is driving China’s multibillion dollar designer toy industry. Its centerpiece is the blind box, a practice of opaquely packaging collectible figurines that sell at $8 a pop, and for Li Shute, a young university art teacher in Beijing, they became an obsession.

“Seeing all the toys carefully arranged in the store filled me with desire,” says Li, recalling her pursuit of Sonny Angels, a baby with a penchant for quirky headgear, and afternoons spent in specialty shops surreptitiously rattling and pinching boxes trying to determine the secrets inside. To date, she owns around 100, though she’s lost count.

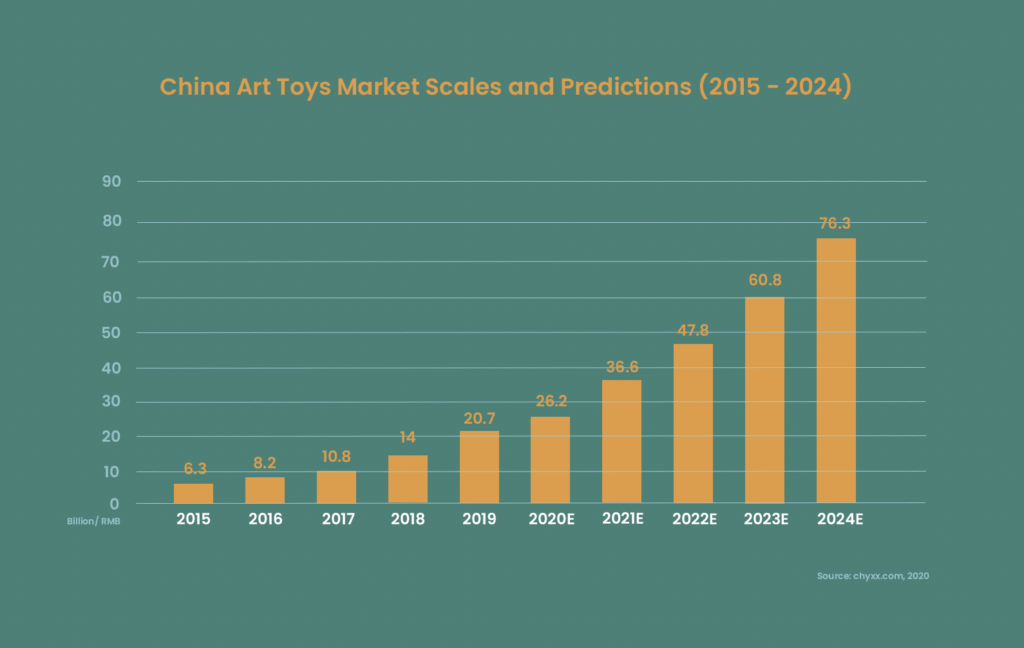

Young, white collar, and female, Li is representative of an exploding fan base that drove a 600 percent increase in blind box sales between 2018 and 2019. While the in-store experience remains important, sales are increasingly shifting online — Chinese e-commerce retailer Tmall ranked “art toys” among their top growing sectors last year.

It’s a trend Chinese cultural institutions are tapping into.

The popularity of designer art toys has exploded in recent years, particularly with young, urban, female consumers. Image: Peter Huang

From Ancient Relics to Designer Collectibles

The Terracotta Warriors may be a priceless wonder of the ancient world, but for their protector, Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum in northwest China, products in their image have real commercial value. Twice in the past year, it’s released limited-edition figurines which reimagine the clay warriors in futuristic hues of silver and purple. Both times, they’ve sold out in minutes on e-commerce platform Taobao.

Another repository of early Chinese history, the Sanxingdui Museum, which houses treasures from the Shu dynasty, has been releasing blind box figurines for over a year. It specializes in turning its bronze bird idols and ceremonial masks into 10-cm vinyl models. Most recently, it released 26 figures, including two mystery models, described by the museum’s marketing department as stylized interpretations of cultural relics. The strategy is working. In 2019 the museum made $1.4 million by selling these and similar products that harnessed its intellectual property.

Beijing’s Palace Museum, one of China’s most pioneering and mercantile state institutions, has released replica stone lions, phoenixes, and empresses.

Sanxingdui Museum in Sichuan Province is one of several Chinese museums turning artefacts into collectible figurines. Image: UNIDUS

Pursuing the blind box craze is part of a broader push by Chinese museums to become more fun and accessible to younger audiences.

“I’m not surprised Chinese museums are tapping into the blind box trend,” says Yilun Zhang, Creative Business Lecturer at Hogeschool Utrecht, “trendy marketing approaches have been key to their overall strategy in recent years,” noting such efforts run the gamut from having Chinese influencers write WeChat articles to launching on Douyin, known outside of China as TikTok, to creating cosmetic products with young brands.

It’s not just Chinese museums getting involved, the British Museum launched a line of Egyptian god figurines in 2019 and revamped the collection for its “Ancient Egypt Pop-up Store” at a high-end shopping mall in Shanghai this summer.

POPMART: Blind Box Tastemaker

No company is more responsible for catalyzing the blind box craze in China than POP MART. Join Chinese Millennials milling about a high-end shopping mall from Shanghai to Shenzhen and chances are you’ll stumble upon a branch of the art toy stores — or one of POP MART’s more than 200 roboshops, toy dispensers styled off Japan’s gashapon vending machines.

POP MART’s speed of growth has been astounding. In the 10 years since launching, it’s captured 8.5 percent of the market, landing it a $2.5 billion valuation and a pathway to file for an IPO on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Success has stemmed from a fine-tuned understanding of Millenial and Gen Z tastes. “The business of blind boxes is closely linked to trending Chinese topics,” says Steffi Noël of Daxue Consulting, a China marketing research consultancy, “POPMART knows this well and asks people on social media what new products it should design.”

Unlike traditional retailers which license the intellectual property (IP) of popular characters — think Disney or Marvel — and develop toy lines, POP MART has created its own wildly popular IPs, most notably Molly, a blonde girl with oversized turquoise eyes and a vapid expression. Molly’s selling point? She has no story and is a blank space for fans to pour their soul into, according to Wang Ning, Pop Mart’s founder.

Millennial Pivot

In this respect, cultural institutions, organizations that strive to weave compelling narratives around the objects and cultures they protect, are well-placed to turn their IP into collectible adult playthings. “It’s a great opportunity to make young consumers think about going to museums for entertainment purposes,” says Noël, “museums follow trends to gain visitors and it’s part of a bigger online strategy.”

Could the short-term buzz generated by marketing campaigns surrounding plastic miniatures overshadow the role of institutions as centers of art and culture? Zhang certainly thinks so, but with traditional museums on a mission to attract younger crowds, it might be a risk worth taking.

Additional reporting by Jiayi Li